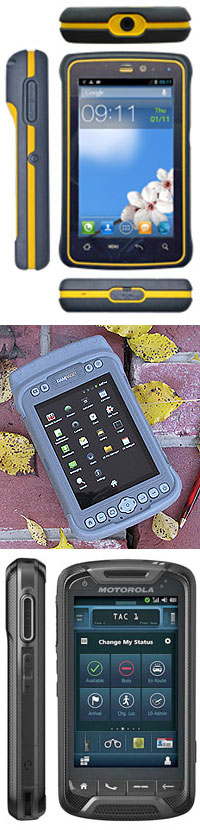

The tablets and handhelds listed in the righthand column on this page are rugged/vertical market devices available with Android. Android is the operating system platform that successfully emulated Apple's ground-breaking iOS with its capacitive multi-touch interface that allowed for effortless panning, zooming, rotating, etc., Apple's "apps" infrastructure, and even the hardware and software layout of Apple products.

Android, however, is no mere copy. It came from people who knew a lot about mobile operating systems. The man behind the project was Andy Rubin who had worked at Apple, Magic Cap, WebTV and then Danger, where they developed the HipTop internet phone. Google bought Android in 2005 and the platform is now handled by the Open Handset Alliance. In just a few years, Android has become by far the dominant smartphone OS. Android had a tougher job on the tablet side where for several years it trailed the Apple iPad by a considerable margin.

Android, however, is no mere copy. It came from people who knew a lot about mobile operating systems. The man behind the project was Andy Rubin who had worked at Apple, Magic Cap, WebTV and then Danger, where they developed the HipTop internet phone. Google bought Android in 2005 and the platform is now handled by the Open Handset Alliance. In just a few years, Android has become by far the dominant smartphone OS. Android had a tougher job on the tablet side where for several years it trailed the Apple iPad by a considerable margin.

Android offers a number of opportunities and challenges in vertical markets.

The opportunity lies in the fact that Android has managed to become the de-facto standard in non-Apple smartphones. Literally billions already know how to use Android devices, sharply reducing training needs. And Google is offering the use of Android for free. In price-sensitive markets, not having to pay a license fee can make or break a product.

Among Android's challenges are legal issues, version fragmentation and Google's increasingly heavy-handed presence on al Android devices. Versions fragmentation is a problem because it makes the Android market nowhere near as cohesive as it appears to be. Older versions are being left behind and often cannot be upgraded, developers are forced to adapt to multiple versions, and so on.  Among legal issues have been Microsoft's success in extracting license fees from Android vendors, a massive Oracle patent infringement lawsuit against Google, and seemingly endless suits between Apple and major Android vendors. Fortunately, as of late 2021, most of the law suits seem to have been settled.

Among legal issues have been Microsoft's success in extracting license fees from Android vendors, a massive Oracle patent infringement lawsuit against Google, and seemingly endless suits between Apple and major Android vendors. Fortunately, as of late 2021, most of the law suits seem to have been settled.

Overall, while the operating platform race is pretty much over in consumer smartphones, it's still unclear which OS will come out on top in mobile computing on the enterprise/rugged handheld computer and on the tablet sides. For high-end tablets, Windows 10 remains a good and safe bet. For ruggedized versions of consumer tablets, the iPad's ongoing success and Microsoft's surface tablets have invited a cottage industry of rugged cases. Initially it didn't look like Microsoft's Surface tablets were going anywhere, but they became a sizable business. All platforms depend on whether developers and customers consider them reliable, dependable and, most of all, secure platforms.

As of late 2021 the initially small number of Android-based rugged mobile devices has grown in leaps and bounds since its beginnings around 2012. While initially manufacturers hedged their bets by offering some of their devices in both Microsoft Windows and Android versions, Android has been gathering considerable steam in tablets over the past several years. However, we still see growing strength on the Windows side as well. Mobile computing historians may recall a similar situation three decades ago when, until Microsoft prevailed, pen computers were offered with either PenPoint or Windows for Pen Computing (though Android abviously did not encounter PenPoint's fate).

The background of Android's vertical market emergence

For many years, almost all vertical, enterprise and industrial market tablets were running some version of Microsoft Windows. Even when new consumer market PCs were sold with Windows 8/8.1 and then Windows 10, in the vertical markets tablets and notebooks were still offered with a variety of Microsoft operating systems. Most stayed with Windows 7 long after Windows 10 was introduced, and many came with various embedded versions of Windows. Some came with Windows 8/8.1 or Windows 10, but also had a Windows 7 "downgrade" option. The latter "loophole" was finally closed when Intel's "Skylake" 6th generation of Core processors was the last one to still support older Windows operating systems. Starting with the 7th gen "Kaby Lake" processors, only Windows 10 was supported.

On the handheld side of things, for several years the situation was needlessly complicated and uncertain. That's because while the great majority of all consumer smartphones run Android (and premium smartphones iOS), a large number number of vertical market handhelds continued with the ancient Windows Mobile/Windows Embedded Handheld, waiting for Microsoft to finally make up its mind about the future of its small system's OS.

Almost inexplicably, Microsoft never offered an upgrade path for its older small device operating systems to Windows Mobile. Windows Phone 7 turned out to be totally consumer-oriented and not backward-compatible with older Windows Mobile and Windows CE applications. And all Windows Phone 7 devices had to have a capacitive touch screen, and that at the time meant no gloves. So Windows Phone 7 clearly was not the future for industrial handhelds, and though Microsoft eventually came out with Windows Embedded Compact 7 and Windows Embedded Handheld 8.1 it was too little too late.

What also complicated matters was that Microsoft moved the Windows Mobile group into the Windows Embedded business, and thus separated it from the Windows Phone group. So for a while, there was Windows Mobile 6.5 (also known as Windows Embedded Handheld 6.5) as well as Windows Embedded Compact 7. As a result, Windows Phone 8 was not only incompatible with the old Windows Mobile, but also with Microsoft's own Windows Phone 7.x. It was a bizarre situation.

Many then expected Windows Phone 8 to have an impact on the vertical mobile handheld market as it represented a clean break with anything that came before it, and also shared components with Windows 8. Unfortunately, the unethusiastic reception of Windows 8 and Windows Phone 8 meant that most verticals stayed with the increasingly obsolete WEH 6.5, or they tried Android.

All of this seemed to change with Windows 10. In 2017, the awkwardly named Windows 10 IoT Mobile Enterprise theoretically became the successor of the old Windows Mobile/Embedded Handheld. But once Microsoft's Nokia Lumina experiment failed and was abandoned, there was very little adoption of Windows 10 in any form on handhelds. Eventually, Microsoft ceased all efforts and exited the small devices OS market in late 2017, casually mentioning Windows 10 Mobile was now in "maintenance mode."

By early 2020, Android held over 80% of the smartphone market, with Google still concentrating almost exclusively on phones at the expense of tablets. Version fragmentation remained a big issue, as was a lack of upgradeability and Google's increasing heavy-handedness in tying more and more of Android to Google and Google services.

On the plus side, rugged Android devices are, for the most part, no longer treated as junior versions of Windows devices. Most new Android handhelds and tablets use near state-of-the-art technology, and the performance gap between consumer tech and rugged devices is no larger that large.

With Windows CE/Mobile/Embedded Handheld gone, Android is the clear (and pretty much only) migration path for older handheld deployments and applications. Increasingly, Android tablets are part of that migration.

As of late 2021, Android continues to make inroads. The migration from old legacy Windows CE, Windows Mobile and Windows Embedded Handheld to Android is big business. Companies like Ivanti and others offer tools like terminal emulation, voice picking and web apps that make migration easy. While Google keeps Android almost exclusively focused on phones and seems mired in an internal Android vs Chrome OS battle, third party hardware providers offer increasingly powerful Android tablets (an example is the Panasonic Toughbook A3).

By early 2023, Microsoft's legacy handheld OS platforms are mere memory; it's all Android on the majority of the world's smartphones and also on almost all vertical and industrial market handhelds. Google's endless version and user interface tinkering remains annoying, as does Google's increasing use of Android for advertising and locking Android users into its own services.

--Conrad H. Blickenstorfer, Ph.D. (updated January 2023)

Android, however, is no mere copy. It came from people who knew a lot about mobile operating systems. The man behind the project was Andy Rubin who had worked at Apple, Magic Cap, WebTV and then Danger, where they developed the HipTop internet phone. Google bought Android in 2005 and the platform is now handled by the

Android, however, is no mere copy. It came from people who knew a lot about mobile operating systems. The man behind the project was Andy Rubin who had worked at Apple, Magic Cap, WebTV and then Danger, where they developed the HipTop internet phone. Google bought Android in 2005 and the platform is now handled by the  Among legal issues have been Microsoft's success in extracting license fees from Android vendors, a massive Oracle patent infringement lawsuit against Google, and seemingly endless suits between Apple and major Android vendors. Fortunately, as of late 2021, most of the law suits seem to have been settled.

Among legal issues have been Microsoft's success in extracting license fees from Android vendors, a massive Oracle patent infringement lawsuit against Google, and seemingly endless suits between Apple and major Android vendors. Fortunately, as of late 2021, most of the law suits seem to have been settled.