This article is about how one company managed to create a successful product in a very difficult market. The company is Matsushita and the product is the Toughbook line of ruggedized notebook computers. Toughbooks are sold business-to-business into corporate and a number vertical markets. The installed user base is currently about half a million. The Panasonic Computer Solutions Company, Matsushita's US distributing arm for the Toughbook line, is growing much faster than the industry average. And they make money. They are profitable.

How can that be?

To give you an example of how difficult it is to succeed in the PC market, just look at IBM itself, the company that introduced the PC in 1981. Hundreds of millions of PCs have been sold since then, yet IBM soon lost the leadership in the market it created, and IBM never really managed to make much of a profit on PCs. And neither did most of its competitors. Clearly, creating a market and selling mass quantities of good products does not guarantee success. Not even if a company has the resources of an IBM, and if the products are of good quality and provide value.

Enter a relatively small team within the giant Matsushita company of Japan. In a veritable case study of excellence they conceived of a way to succeed in the PC market where others could not. They did that by analyzing the market, finding a niche, and then building just the right product.

Enter a relatively small team within the giant Matsushita company of Japan. In a veritable case study of excellence they conceived of a way to succeed in the PC market where others could not. They did that by analyzing the market, finding a niche, and then building just the right product.

They did everything right. The right niche, the right team, vision, perseverance, and probably a degree of luck. Everything clicked, and in one of those rare instances where everything falls into place, the Toughbook became one of the true success stories in mobile computing.

At Pen Computing Magazine, we have been following the Toughbook line almost since its inception and, over the years, have reviewed every model. So when we got an invitation to take a closer look at just exactly how Panasonic managed to do it, we jumped at the opportunity.

My subsequent travels took me to Japan where I visited Panasonic facilities in Osaka, Kobe, and Tokyo. I also examined Panasonic's stateside service facilities in Kansas. Panasonic was extremely cooperative and gave me a chance to examine every aspect of the process, and talk to everyone involved.  I had almost unprecedented access to every facility, and I found everyone being very forthcoming in answering every question, even the difficult and uncomfortable ones.

I had almost unprecedented access to every facility, and I found everyone being very forthcoming in answering every question, even the difficult and uncomfortable ones.

But first let me present a brief overview of the Toughbook line for readers who may not already be familiar with the Toughbooks. Toughbooks are "niche" products. The line includes notebook computers that range from slightly more sturdy than standard notebooks all the way to very rugged notebooks for use by the military and other markets where toughness and reliability are mandatory.

They fill the market where computing power is needed, but where standard consumer products just can't make it. Utilities come to mind, insurance, healthcare, telecommunications, transportation, the government, field service and sales. That's how it started. Panasonic later found that corporations also were getting tired of the very high failure rate of notebook computers, and so they built high-reliability Toughbooks for that market as well. And recently, the line has been augmented with additional products such as wireless displays and a handheld computer. In terms of sales, the Toughbook line is relatively small, perhaps US$300 million a year.

So how did the Toughbook come about, and how could it happen within a giant industrial complex like Matsushita, a no-nonsense manufacturing company famous for no-nonsense products? How could it happen in an almost US$60 billion company that cranks out refrigerators and microwave ovens with the same cold efficiency Toyota employs to crank out Camrys and Corollas? A company that perhaps lacks the playfulness and marketing savvy of arch rival Sony but makes up for it with a blue collar work ethic that's second to none?

So how did the Toughbook come about, and how could it happen within a giant industrial complex like Matsushita, a no-nonsense manufacturing company famous for no-nonsense products? How could it happen in an almost US$60 billion company that cranks out refrigerators and microwave ovens with the same cold efficiency Toyota employs to crank out Camrys and Corollas? A company that perhaps lacks the playfulness and marketing savvy of arch rival Sony but makes up for it with a blue collar work ethic that's second to none?

The answer is that it was extremely unlikely to happen. It came about because a man and his team of enlightened individuals had a vision, and made that vision a reality by skillfully tapping into all the resources a giant industrial complex could provide. What that team did is the exact opposite of the way things are done today.

They did not farm out the entire design and manufacturing to OEMs or contract manufacturers. They did not go on a shopping spree to gather together the cheapest components from the lowest cost suppliers. They did not delegate and farm out everything until they, like most US computer companies, were merely marketers.

Instead, they turned a perceived weakness into a strength. All Toughbooks are conceived, designed, built, and tested right there at Matsushita's own facilities. When they needed special batteries, they simply stopped by Matsushita's battery division.

When they needed optical drives, well, Matsushita makes the best. When they needed a special case, Matsushita is a leader in manufacturing processes and one of the world leaders in magnesium casting. And then they put it all together right there at the most impressive Panasonic Computer manufacturing plant outside Kobe, Japan.

The result is the real thing. Just like a Toyota is the real thing and in a league of its own, a league that the Kias and Daewoos and Hyundais of the world aspire to but cannot reach. Like Toyota, Matsushita is the real thing. 290,000 worldwide employees, 14,000 products, 320 companies, and an annual budget of US$4.4 billion for research and development alone.

Things weren't always that good. Panasonic tried it the conventional way first. They made portable PCs in the early 1980s but couldn't make a profit. Between 1983 and 1990 they were a channel OEM, making computers for other companies. In 1992, Panasonic decided to change the focus of their PC operation and go for corporate and ruggedized sales to government, corporate and a number of special vertical markets. At Pen Computing Magazine, we've seen many rugged products over the years. They ranged from computers that looked more like science projects, to honest but underfunded efforts, to the real thing. With Matsushita's resources, it's clear that the Toughbooks falls into the third category.

I began my tour of Matsushita's Panasonic facilities with a visit to the Matsushita Hall of Science and Technology, which is part of the company's Moriguchi City complex in Osaka, Japan. The hall is a combination of Matsushita history, its many current concepts and products, a number of technology demonstrations, and a peek at future products.  All in all, there are about 300 technologies and products, all chosen to highlight the company's dedication to research which, as a brochure points out, "is for the happiness of mankind."

All in all, there are about 300 technologies and products, all chosen to highlight the company's dedication to research which, as a brochure points out, "is for the happiness of mankind."

This sounds flowery to Western ears, but it is very much in sync with my impression from earlier visits to Japan. The Japanese view technological progress as something that increases happiness and well-being and generally and genuinely improves society. Sounds good to me.

My next stop was at the Moriguchi Office of Matsushita's Information Technology Products Division, the entity responsible for all Toughbook computer products. I met with the General Manager of Marketing and Sales, Mr. Hide Harada, and the General Manager of the Technology Center, Mr. Toshiuki Takagi.

The picture to the right shows Mr. Yoshi Yamada, father of the Toughbook, flanked by his top lieutenants.

I learned that although Panasonic's considers its earlier forays into the PC market disappointing, the company actually sold almost two million notebook computers since 1987. Half a million of those have been rugged units, with 130,000 sold in the year 2000 alone. I also learned that the computer group has 250 engineers focusing solely on mobile and wireless technology and that the current capacity of the computer production facility is 2,000 units per day on ten lines. All core manufacturing and R&D is done in Japan. There are some foreign assembly facilities, and also a manufacturing facility in Taiwan that makes one of the Toughbook models. Facilities in the UK and the United States handle configuration and service.

Mr. Harada recapped the history of the computer division and related how in 1992 they decided to identify niche markets and eventually specialized on corporate and ruggedized notebook sales to government, corporate and vertical markets. 1996 was a milestone year as they received a request from Lucent for Toughbooks with integrated wireless capabilities.

Rather than simply using wireless PC Cards they decided to engineer wireless radios into the device. The result was an order for 7,000 Toughbook 25s using the Ardis and Motient wireless networks. Subsequently, plenty of research went into integrating wireless components into all Toughbook products. At the same time there was a constant effort to make products thinner and lighter without giving up battery life and ruggedness.

To reflect the solutions-oriented approach, Matsushita decided to change the name of the group from Panasonic Personal Computer Company to Panasonic Computer Solutions Company. While the initial focus of this solutions-based marketing approach was on Japan where the Toughbook line is sold under different names and includes some lighter duty models, it quickly expanded to the UK, the United States, and will soon be introduced in Germany and other countries. Panasonic's new approach was different, just like Fujitsu Personal Systems' approach was different, but it definitely put the Toughbook brand on the map. At a past PC Expo trade show a Toughbook 34 was being horribly abused yet survived, garnering much media coverage.

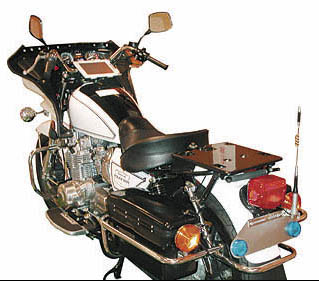

The essence of a "Toughbook" is that each is designed and built to withstand abuse that no ordinary notebook could survive (the image shows a police motorcycle equipped with a wireless Toughbook 07). That involves plenty of research and also plenty of testing and certification. Panasonic performs "torture testing" in its own facilities, according to both Japanese and US test procedures, and the products also undergo independent tests. In the US, those tests are conducted by the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio (swri.org), a non-profit testing agency whose clients include NASA and US auto manufacturers. SWRI performs MIL-STD 810 ruggedization testing.

The essence of a "Toughbook" is that each is designed and built to withstand abuse that no ordinary notebook could survive (the image shows a police motorcycle equipped with a wireless Toughbook 07). That involves plenty of research and also plenty of testing and certification. Panasonic performs "torture testing" in its own facilities, according to both Japanese and US test procedures, and the products also undergo independent tests. In the US, those tests are conducted by the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio (swri.org), a non-profit testing agency whose clients include NASA and US auto manufacturers. SWRI performs MIL-STD 810 ruggedization testing.

It is important to understand that Panasonic's Toughbook computers are not consumer products but are geared towards mission-critical applications and uses. And while Toughbooks do not sell by the millions, orders can be quite large. Among the international success stories Panasonic likes to share are British Gas which bought 7,000 CF-27s in a customized solution that packed the computer, wireless communication and a printer into a special suitcase-like case. British Gas vans have those systems onboard and thus have instant access to parts lists, schematics, and manuals. In Spain and Canada, McDonalds uses the Toughbook 07 for taking orders. And Bell Canada is using the wireless CF-07s for field maintenance.

Throughout the presentations I was surprised at the complete openness with which Panasonic discussed the many ways they employ to detect and improve weaknesses in their products. For example, the US Coast Guard is interested in Toughbooks, but the inevitable salt water exposure required a battery of special tests. The tests resulted in substantial corrosion and salt build-up on the Toughbooks (see above). Panasonic engineers recorded the results and went back to the drawing boards to create a special model for the USCG that could stand up to use in saltwater environments. This includes special resistant paints, anti-corrosive greasing and coating, stainless steel screws, airtight gaskets, and sophisticated chemical counter measures against electric corrosion. The retest is still under way, but preliminary results show great improvements, and also Panasonic's willingness to adapt their technology to their customers' needs.

The image to the right shows keyboard torture testing at Panasonic's Moriguchi plant.

Another important aspect of ruggedness is shock absorption. There is much more to that than simply wrapping a component into foam rubber or inserting a bit neoprene. It involves researching and testing the absorption properties of hundreds or materials and then picking the right one.  While a material's primary shock absorption qualities are important, optimal results also depend on how it is shaped and where it is applied. Panasonic settled on a two-layer approach, with each having different absorption properties. After testing numerous variations of thickness, cut angles, and adhesion materials, they finally arrived at materials, shapes and layer combinations that worked best.

While a material's primary shock absorption qualities are important, optimal results also depend on how it is shaped and where it is applied. Panasonic settled on a two-layer approach, with each having different absorption properties. After testing numerous variations of thickness, cut angles, and adhesion materials, they finally arrived at materials, shapes and layer combinations that worked best.

Even the paint applied to the outer and inner surfaces of a Toughbook makes a difference. Hardness of paint is measured by the same standard as the graphite hardness of a pencil. Current paint hardness is 3H, but the engineers aim for 6H which means that the paint cannot be scratched by a 6H pencil. For plastics, the acidity in sweat can discolor or break down the paint or the plastic itself.

PH levels are important and must be taken into consideration when specifying such materials. Since heat dissipation is always an issue with notebook computers, heat-insulating paints can minimize heat on metal bodies. Water-shedding paints can make water pearl off and a device so painted will be more resistant to dirt. But each change may impact other properties. I had no idea how much work went into perfecting every aspect of this.

PH levels are important and must be taken into consideration when specifying such materials. Since heat dissipation is always an issue with notebook computers, heat-insulating paints can minimize heat on metal bodies. Water-shedding paints can make water pearl off and a device so painted will be more resistant to dirt. But each change may impact other properties. I had no idea how much work went into perfecting every aspect of this.

With regard to wireless, Panasonic prides itself on using numerous standards in response to customer needs: Mobitex and DataTAC, CDPD, GSM/GPRS, and wireless LANs. Research is now on emerging technologies such as Bluetooth and faster wireless LAN protocols.

Since Toughbooks may be used indoors and outdoors, Panasonic currently uses both transmissive and transflective technologies. Brightness and contrast are always big issues, and Panasonic engineers experiment with different fluorescent tube mounts, backlights, reflectors, and even multiple lamp 1000 NIT systems for stationary use in a never-ending quest for perfection.

During my visits, I had a chance to meet with Mr. Yoshi Yamada, the director of the computer division and the father of the Toughbook. Yamada is a remarkable man who succinctly and concisely explains the thought process he and his team went through. Like the computers he creates, Mr. Yamada is tough and all business. I immediately knew that this man would never build or authorize anything that he didn't believe in, anything that he did not feel was beneficial for his customers. In many ways, he reminded me of Jeff Hawkins, the brilliant yet humble creator of the Palm Pilot, and arguably the PDA.

My tour also allowed me a chance to visit the various divisions that contribute parts to the Toughbook. Matsushita's AV Technology Center, for example, creates some of the world's most advanced optical drives. It stands to reason that those drives will work extra well in Toughbooks because they came from the same people who make the Toughbooks. Which means that they're probably better integrated, better tested, and more suitable for the computer than a generic third party device.

One of the most visible characteristics of Toughbooks is their magnesium case. With the exception of Walkabout's use of "milled aircraft grade aluminum" for their Hammerhead pen tablets, few computers are as identified with a particular material as Toughbooks are with magnesium. And Panasonic certainly made the most of this association. In the Toughbooks, magnesium is a design element and a structural feature. It's beautiful to look at and very tough. Highlighting it was one of the Toughbook team's great marketing ideas. However, working with magnesium isn't easy. It requires great expertise and a major investment in R&D and equipment.

Here again, having the full might of the giant Matsushita company at their disposal is invaluable as I saw when I met with Mr. Yukio Nishikawa at Matsushita's Production Core Engineering Laboratory. The mission of Mr. Nishikawa's lab is to develop new manufacturing processes that advance the state-of-the-art, create cost savings, and place emphasis on recycling and recovery which is becoming very important given Japan's tough new recycling laws.

Due to magnesium's properties, the metal is widely used by Panasonic in products ranging from cellphones to computers to big screen TVs. Magnesium-light and readily available-is also rigid, conducts well, shields electromagnetic waves, and is easily recyclable. Add to that the much higher tensile strength and elasticity and it's clear why magnesium has become a desirable material. Most companies use a die-cast process that uses environmentally harmful SF6 gas to prevent the metal from burning.

Panasonic uses thixo-molding, an injection process invented by Dow Chemical in the US, that uses melted magnesium chips and argon gas and offers increased safety and cleanliness, and higher quality parts. I was one of the few outsiders ever to get a tour through Panasonic's magnesium foundry with its thixo-molding machines. An impressive sight indeed.

Earlier, I mentioned that Matsushita even makes the batteries that go into the Toughbooks. A tour through Matsushita Battery Industrial company (16,000 employees and factories in 14 countries) conducted by Mr. Kuniharu lizuka revealed an unbelievably complex and complicated facility that is sort of like the ultimate Rube Goldberg machine.

Earlier, I mentioned that Matsushita even makes the batteries that go into the Toughbooks. A tour through Matsushita Battery Industrial company (16,000 employees and factories in 14 countries) conducted by Mr. Kuniharu lizuka revealed an unbelievably complex and complicated facility that is sort of like the ultimate Rube Goldberg machine.

Batteries are born in a process that takes them through a sequence of impossibly complex machines where the chance of something going wrong seems endless. The line I saw was for CGR18650 Lithium-Ion rechargeables where positive electrode, negative electrode, and separator material are first rolled tightly, then insulated, and inserted into a metal bullet casing. It then gets terminal contacts and is filled with electrolyte that settles through a number of steps. A cap is put on, the whole assembly is crimped, sealed, and then shrink-wrapped into a plastic shell.

Numerous tests are conducted at every step. Whenever something goes wrong and a warning sound goes off, a specialist immediately diagnoses and fixes the problem. Environmental conditions are crucial and meticulously maintained. It is hard to even imagine the complexity of this assembly line. Then the battery goes into a Toughbook.

During my time at Matsushita I jotted down some 10,000 words of notes and impressions. It could easily have been 20 or 50,000. This feature represents just a summary, a brief look at a project gone right, one where smart people did everything right and came up with a product that meets and exceeds the needs of both the customer and the company that makes it.

I am sure other fine companies have stories to tell, but I must say that the Panasonic Toughbook story ranks right up there as a prime example of how things ought to be. -- Conrad H. Blickenstorfer, 2002

http://www.panasonic.com/toughbook